Zero

The sun is Zero. Zero is white. The desert Zero. The sky above Zero. The night.

Heinz Mack, Otto Piene, and Günther Uecker, 1963

The best image of Zero, probably, is the one connected with the exhibition at Galerie Schmela in Düsseldorf in 1961, marking the moment of surfacing after a few years of underground existence: nothing in the gallery, everyone in the courtyard and the street, an entire smiling throng, beer bottles, a liberating atmosphere, balloons with the word “Zero” about to be released into the sky, no artists, or all artists, an irrepressible and visible desire to break the rules and be happy.

The founding of Zero, which dates back to 1958, initially by Heinz Mack and Otto Piene (Günther Uecker joined forces with them in 1961), precisely coincides with the urgency of certain existential questions the community of intellectuals—in Germany, but also elsewhere—was raising after the end of the war and the first postwar reconstruction.

The system of values—all values, thus including those of art—needed to change, to avoid any possible encoding that would first of all construct a “style” and then, precisely, a “code” that would lead to a new fixity: the anarchy of Zero becomes a response assembled and emitted by groups that—not by chance—spring up in just this period, and insist on the liberating and libertarian aspect of art, each in its own way. But what do we mean by the “anarchy of Zero”?

The main need of the men and women of Zero is to “live,” and Piero Manzoni had summed it up nicely in the conclusion of his text “Libera dimensione” published in Azimuth no. 2, in January 1960, a passage constantly and justifiably quoted: “there is nothing to say: there is only to be, only to live.” Though it does not strictly belong to the literature of Zero, with whom Manzoni, moreover, had immediately come into contact, already in 1959 that phrase and the whole text could be taken as a paradigm of what Zero wanted and continued to express with few writings, but with ongoing deployment of that exhortation: “live!”. Were we to stop here, however, we almost seem to be faced with a movement of opinion, an existentialist attitude, a vaguely political trend not yet gathered in a group or, worse, in a party of small numbers, obviously positioned to the left of the left… Little to do with art, then, and much to do with its own existence coming to grips with the “moral wreckage,” even prior to the physical wreckage of a Europe still in need of reconstruction.

In Zero there are no rules or banishments, no dogmas to share or stated enemies to fight, no manifestos but at most “hymns”: how else to define the most famous text, which appeared inscribed in a black circle in 1963, which concludes “Zero is silence. Zero is the beginning. Zero is round. Zero is Zero”? Yet Zero stood out and still stands out in various ways, though all of them are valid and none of them are alternatives to others.

The most innovative characteristic is undoubtedly that of being a transnational trend: had the movement been limited to the three founders and the circle of German friends, it would have just been another of the many movements— some quite remarkable—connected to a cultural model consistent with historical-geographical roots (just consider, to take one postwar example, the so-called New York School) or more simply contingent factors (the components of Gruppo T or Gruppo N always gathered at the same bar…).

Instead Zero, though not scorning bars or friendly gatherings, was based on universal concepts—like almost all the neo-avantgardes of the post-war era—and put this universalism into practice through transnationalism, i.e. through its transformation into a nomadic movement, a sort of “blob,” a drop of mercury on the map of Europe (and beyond Europe, if we consider the American and Asian outcroppings of George Rickey, Robert Indiana and Yayoi Kusama). Of course urging to get beyond national boundaries was the order of the day, but no one else in the field of art pursued this goal with such determination and success, with perhaps the exception of Fluxus, for which it might be worth assessing its possible derivation precisely from Zero (after all, Wiesbaden 1962 is not so far from Düsseldorf 1961…). To this end, certain operative attitudes were necessary, first of all that of an almost nonexistent hierarchy, a development along horizontal rather than vertical lines, making the group more similar to the postmodernity of the web than to the modern approach of ranked organization: in practice, Zero was really a network of intellectuals and artists who have demonstrated the existence of a European cultural connective tissue with shared objectives, above all the renewal of the language with which one could and should look at the world and, as a result, interpret it. Because the language used was precisely the heart, the connective tissue of the connective tissue of a new artistic Europe: there are no precise directives, but there is certainly a sort of “atmosphere of family” in every exhibition, almost as if every artist, in the autonomy of his or her research, had reached the same conclusions, as also happens in science when researchers who do not know each other make the same discoveries.

The term ZERO marked the coming of a new, optimistic kind of art. While the ZERO movement was under formation, Dutch artists Armando, Jan Henderikse, Henk Peeters, Jan Schoonhoven, and herman de vries established the Nul group in the Netherlands. Like-minded artists in Belgium, such as Walter Leblanc were also formulating similar artistic strategies.

Leblanc unquestionably stands among these masters: he focused his investigations on the structural aspect of the image, laying aside traditional notions of painting and sculpture and exploring it through a range of unusual materials such as nails, mirrors, metal, and plastic.

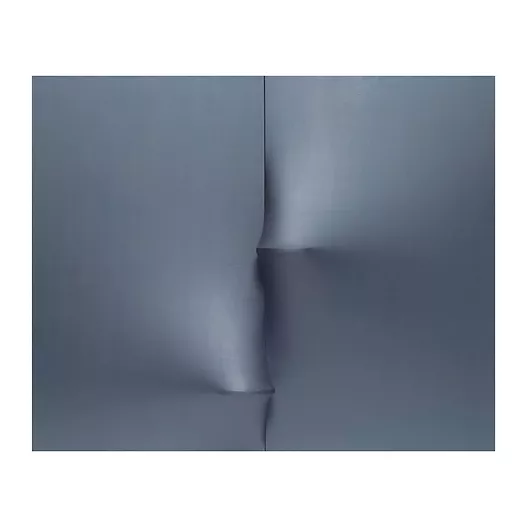

The same approach involved also Italy along with Agostino Bonalumi or Enrico Castellani: artists share the thematic focus of space, light and movement, focusing on the variability and dynamism of the subject and the consequences of the spectator’s participation in the work of art.

Together, the artists began to organize exhibitions in galleries, museums, and in their own studios.

HEINZ MACK

Lichtrelief (Light Relief), 1961

aluminium relief on board

91.5 x 73 cm

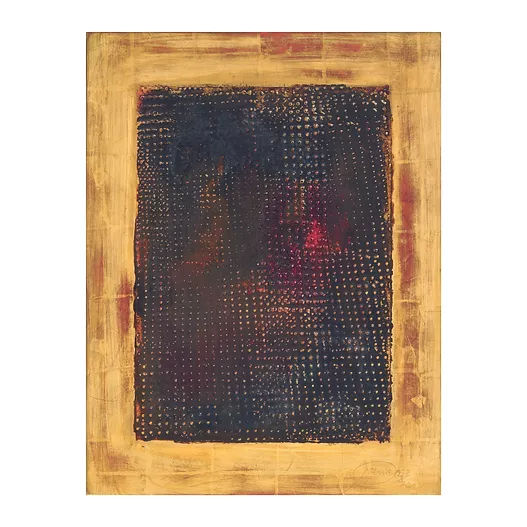

OTTO PIENE

Untitled, 1958-1972

rasterbild: mixed media and traces of fire on wooden panel

50 x 42 cm

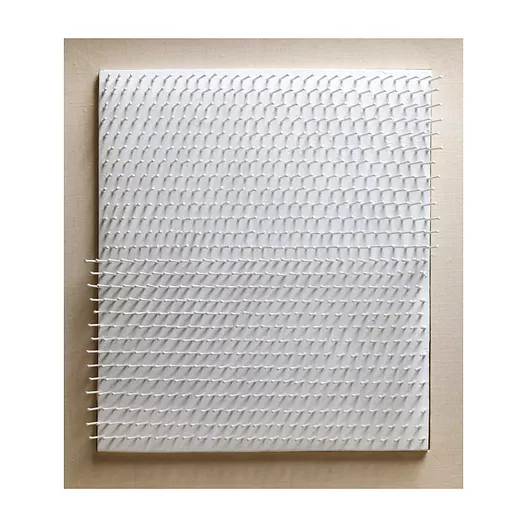

herman de vries

V72-142 S random objectivation – random stromingsvelden, 1972

wood on construction panel, white acrylic paint

60 x 60 x 2.5 cm

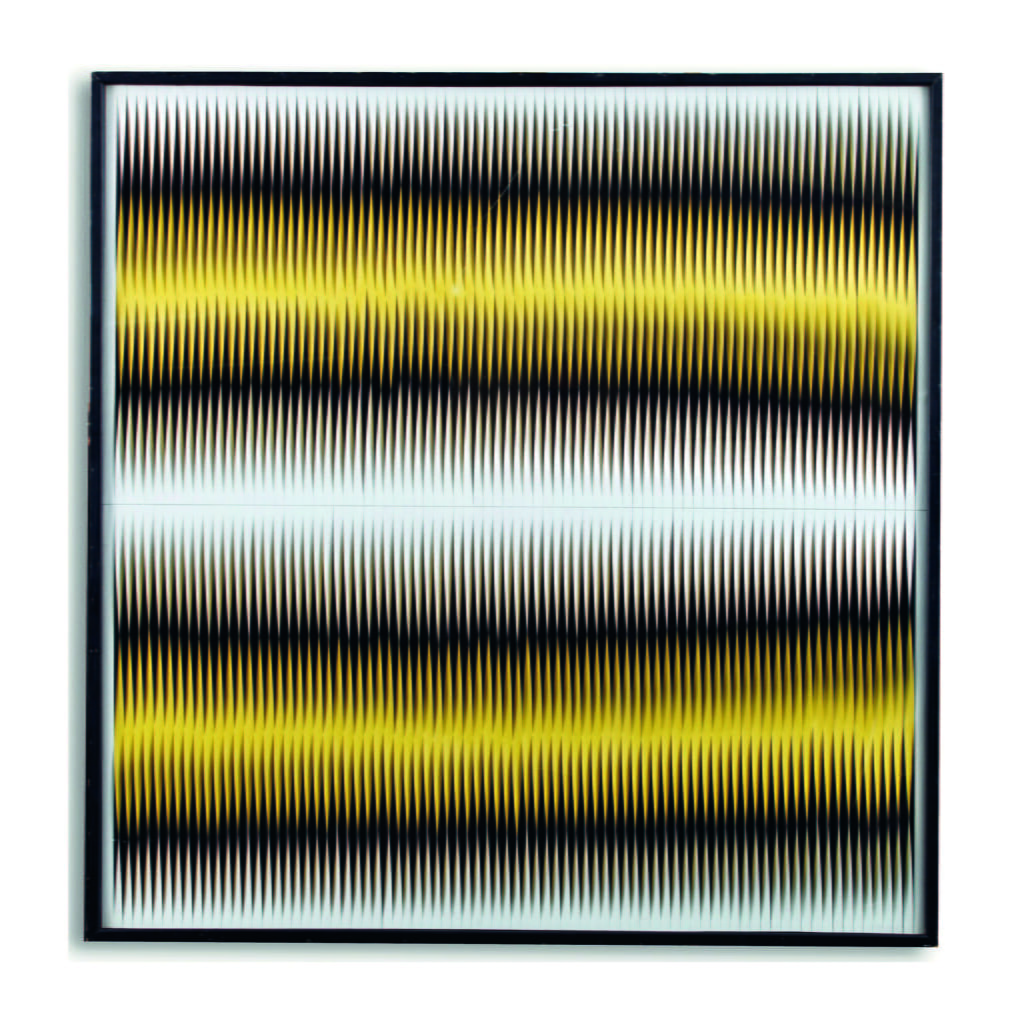

WALTER LEBLANC

Mobilo-Statique, 1962-1965

polyvinyl on board in artist’s frame

130 x 127 cm